Setting the Stage for a Fight: Enlisting T-cells to Combat Multiple Myeloma

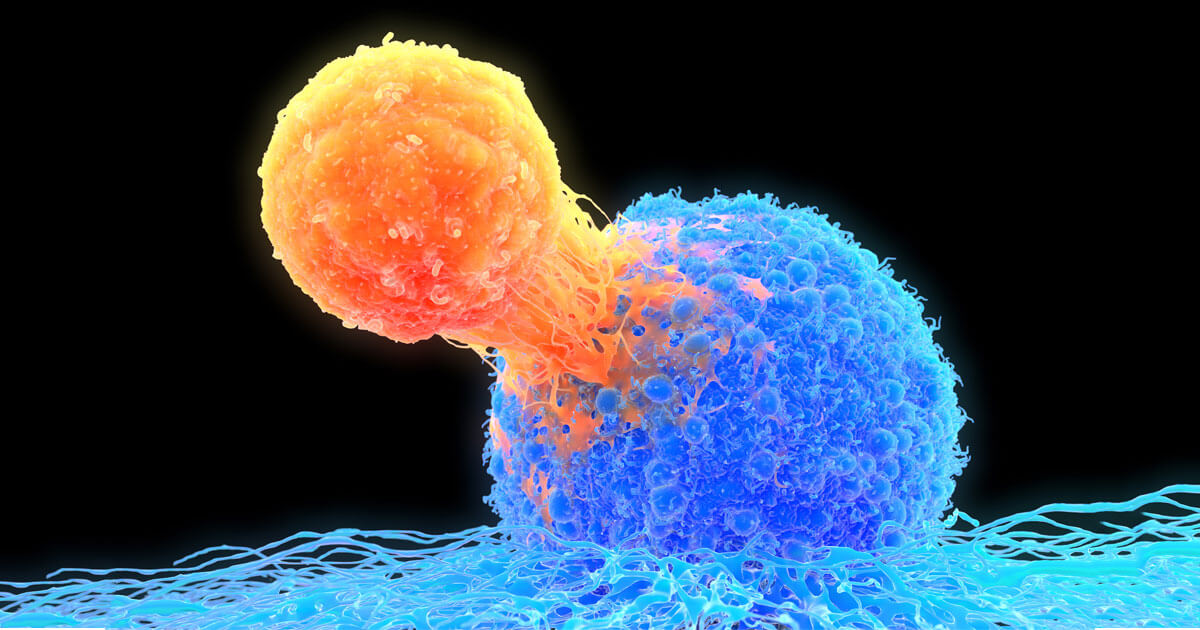

Caption: T-cells (orange) can be redirected to engage and destroy cancer cells (blue) through the use of bispecific antibody technology, which enables a bridge to be formed between surface proteins overexpressed on tumor cells and T cells. (Getty/ illustration)

In our immune system, subsets of T-cells exist that are “professional killers”. They’re constantly patrolling the body to eliminate problem cells, such as those that may turn cancerous or are infected by viruses. But cancer, as we know, can be stealthy. As it grows, it deploys a series of “tricks”— many resulting from genetic mutations— that enable it to evade detection and destruction by immune cells.

But a promising drug technology is helping to re-engage our immune system’s natural cancer-fighting abilities. Known as bispecific antibodies, these protein drugs are made by combining two different binding arms— one that recognizes cancer cells and the other T-cells. When these two cell types are pulled together by the bispecific, the T-cell is activated to destroy the tumor cell. “If we can engage the T-cell, and tie it to a tumor, it should kill whatever is in front of it,” says Michael Eisenbraun, Director - Cancer Vaccines and Immunotherapeutics, Oncology at Pfizer’s La Jolla, Calif. research site. “In some cases, the cancer has spent years deploying multiple strategies to avoid attack, and we’re bringing the immune system back into play.”

‘‘Encouraging responses’’

And this innovative approach is generating hope for patients with the blood cancer multiple myeloma (MM). Although there have been many advances in the treatment of multiple myeloma in the last decade, many patients either do not respond to, or eventually become resistant to existing therapies. But in a recent Phase 1 clinical study, Pfizer’s bispecific antibody that targets BCMA, a protein that is highly expressed on myeloma cancer cells, showed early positive results. “We’ve seen encouraging responses in patients that have failed available therapies,” says Harman Dube, Asset Team Leader in Oncology at Pfizer’s La Jolla, Calif. research site.

As the study enters Phase 2 testing this month, Pfizer has obtained fast track designation with the FDA to help speed up its development. “With such a high unmet need for this devastating cancer, it’s a critical step forward in getting this potential treatment out to patients as quickly as possible,” adds Dube.

Taking T-cells to the next level

The bispecific antibody approach builds upon earlier therapies that also seek to re-enlist the cancer fighting abilities of T-cells. Checkpoint inhibitors, another class of immunotherapies, help release the brakes on these killer cells so they can attack cancers. But, in order for these medicines to work, patients need to have specific T-cells that can recognize the cancer tumors. “Not everybody has those cells, so checkpoint inhibitors don’t work as well for everyone,” says Eisenbraun.

The hope with bispecific antibodies, however, is that they can enlist any type of T-cell circulating in the body. “Because your body is filled with billions of T-cells, it gives us this standing army of cells that we are trying to engage against the cancer,” says Eisenbraun.

Another type of immunotherapy, chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy has shown promise in selectively fighting tumors. Cancer patients have their T-cells harvested, and then engineered in the lab to selectively target tumors, before they’re re-infused into patients.

But in most cases, this treatment must be individually customized for each cancer patient, which can be costly and time-consuming. By contrast, the BCMA bispecific antibody doesn’t require any customization. “What we’re doing here is off-the-shelf, we don’t need to know the patient ahead of time to develop this drug,” says Eisenbraun.

Looking ahead, Pfizer has an additional bispecific antibody, in Phase 1 clinical studies in an area with high unmet need. Pfizer is among the first companies to explore developing a bispecific that attacks solid tumors, which are generally more