Could Diversity in Clinical Trials Be the Key to Understanding Liver Disease?

In a New Yorker article about how evolutionary psychology findings are usually based on surveys of undergraduates, Anthony Gottlieb wrote, “American college kids, whatever their charms, are a laughable proxy for Homo sapiens.”

Biomedical research can suffer from a similar bias: Subjects don’t always represent the full range of patients in terms of gender, race and ethnicity. But why is it important to have diversity among subjects in clinical trials? One benefit is that involving a diverse group of research subjects allows scientists to tease out the sometimes subtle, but at times important, interplay between genetics and lifestyle that can cause disease.

Sometimes the connection between ethnicity and a medical condition is straightforward: Tay-Sachs disease, for instance, is a fatal genetic disorder caused by defects on a gene on chromosome 15. The incidence of Tay-Sachs is much higher among those of Ashkenazi Jewish descent than it is among other populations. Since people have two copies of this gene, if both parents carry the defect, their child has a 25 percent chance of having Tay Sachs.

But most of the time diseases are not the result of a single gene, and are instead influenced by a combination of genetic and lifestyle factors. Understanding why a particular condition disproportionately affects a particular ethnic group can provide a useful clue for researchers looking for ways to treat the disease.

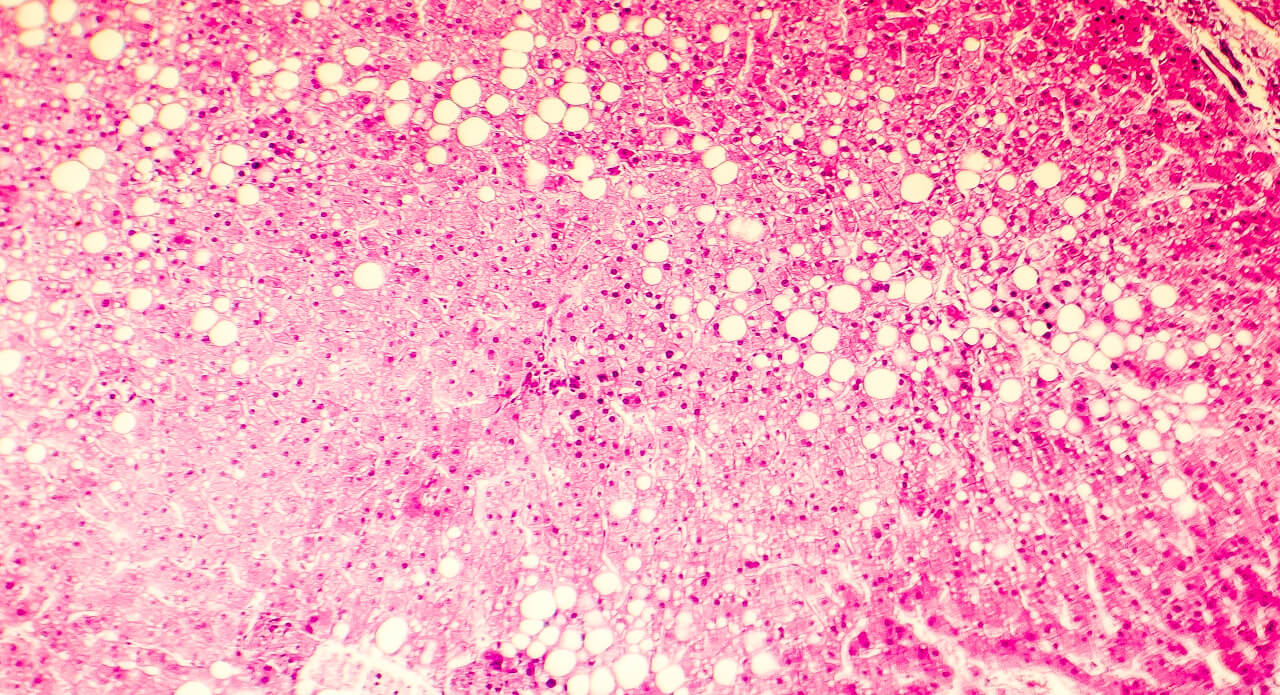

Consider nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), a condition in which fat builds up in the liver and affects an estimated quarter of the world’s population. In some cases, the excess fat in the liver can lead to inflammation, fibrosis, and permanent liver cell damage (cirrhosis). When there is higher than normal amount of fat in the liver that is not related to excessive alcohol consumption, it is called is nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). A subset of this condition called nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) that has both high liver fat and inflammation (swelling) and fibrosis (scarring) that causes a stiff liver. Over time, NASH can lead to cirrhosis, the 12th leading cause of death in the US.

Estimating the prevalence of NASH is not a perfect science given the inherent approach of diagnosis by exclusion and lack of uniformity in tools used for diagnosis — though a needle biopsy is considered the ‘gold’ standard. However, researchers have been able to use imaging techniques such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to estimate the prevalence of NAFLD more broadly.

And because studies have focused on recruiting a diverse group of patients, researchers now know that NAFLD is more common among Hispanics. One study, for instance, found that NAFLD was highest in Mexican-Americans (21.2 percent), followed by non-Hispanic whites (12.5 percent) and non-Hispanic blacks (11.6 percent).

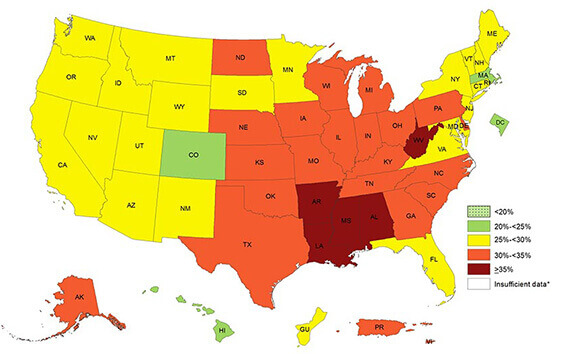

This 2016 “heat map” from the CDC shows the prevalence of obesity across states and territories. Because of the connection between excess weight and fatty liver disease, Neeta Amin’s NASH study was centered in the deep south, where 35 percent or more of adults identified themselves as obese. (Source: cdc.gov)

But it’s also associated with obesity, type 2 diabetes, dyslipidemia, and hypertension, says Neeta Amin, PharmD, a clinical lead in Pfizer’s Kendall Square site who studies NAFLD and NASH.

Some might assume that certain diets typical of Hispanic cultures might contribute to obesity, which is linked to NAFLD and NASH. But it’s not so simple, says Amin. “Many people say that fatty liver disease is a matter of changing your diet, exercising more, and making that long-lasting change in lifestyle,” she says. “I’m not quite sure that the biology suggests that. It’s a disease that isn’t strictly phenotypic. You can be lean and athletic-looking and have NASH. Not all patients fit neatly inside one box.”

Better understanding the link between NAFLD and ethnicity needs inclusion of more diverse groups of patients in clinical trials. That’s why diversity was one of the priorities for the global, Phase 2a, dose-ranging trial that Amin’s team designed. In this ongoing trial, Amin and her team are tracking recruitment not simply according to whether subjects have NAFLD, but also according to sex, age, race, and ethnicity. Selection of sites included in the study accounted for the published CDC “heat map” of the prevalence of obesity, and Type 2 diabetes in the US, says Amin.

That same trial is also a pilot study for Ricardo Rojo, Pfizer’s Global Lead of Diversity in Clinical Trials who is based in Groton, Connecticut. The recruitment to date has actually exceeded the targets Rojo had set for inclusion of Hispanics, African-Americans and Asians in this trial. “In general, there’s a lot we don’t know right now about how various groups respond to drugs,” says Rojo. “But I’m optimistic we’ll fill this void.”

As Amin and her colleagues untangle the knot of factors leading to NAFLD and NASH, they’re joining the movement to make sure that clinical trials include—and are not merely a proxy for—all patients affected by these illnesses.