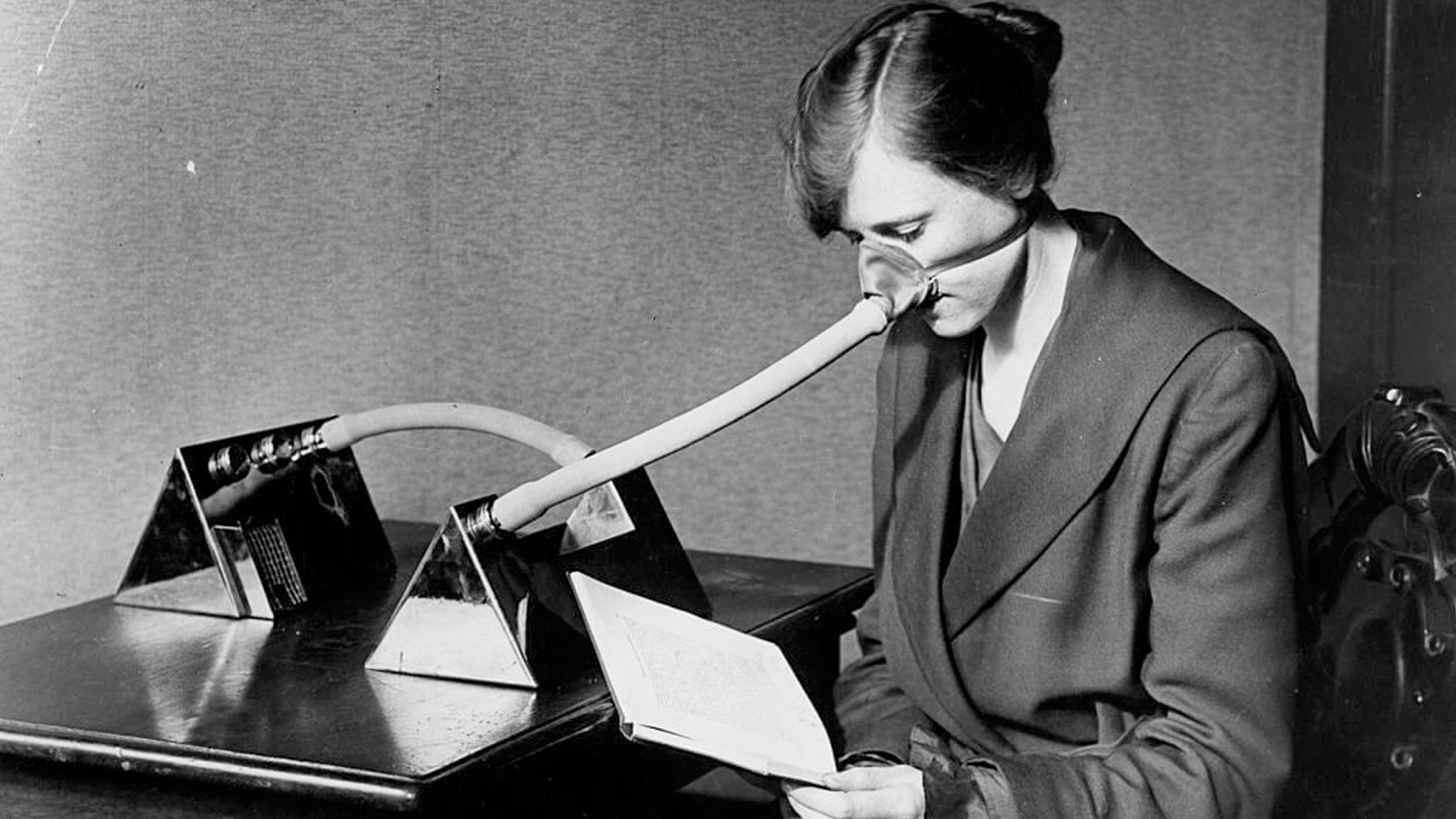

Flashback: Spanish Flu Mask

(Topical Press Agency/Stringer)

At the close of WWI, an estimated 50 million people died from the Spanish flu. Masks were the uninfected’s main line of defense.

Patient zero of the Spanish flu may have been a soldier in WWI, who accidentally carried his virus back into the densely packed military encampment in Fort Riley, Kansas. From there, the infected would have marched across the battlefields of Europe and beyond, carrying the disease with them. In the end, Spanish flu infected a full fifth of the world’s population. An estimated 50 million died of the disease worldwide, from remote Artic villages to isolated Pacific Islands. Three times more people died from the flu, in fact, than from WWI itself.

When the pandemic raged between 1918 and 1920, medical professionals believed that the flu was caused by bacteria. It might not have mattered much if they knew it was a virus at fault—antivirals didn’t exist yet and the flu vaccine had not been developed.

Theaters, churches, and other closed-in public places were shuttered, in some cases for an entire year, lest the bacteria spread in such tightly packed spaces. Even funerals were limited to 15 minutes.

People were asked to wear masks, usually made out of fabric, in public as a first line of defense against contracting and transmitting the disease, and were denied admittance to streetcars, offices, and other public places if mask-less. Above, a woman dons a mechanical nozzle mask in February of 1919.

People tried all sorts of secondary defenses in the event their masks failed. Pamphlets suggested chewing food carefully and avoiding tight clothes and shoes, and there was a surge of support for legislation that would ban public coughing and sneezing. Home remedies included gargling a mixture of sodium bicarbonate and boric acid, stuffing salt up noses, and eating onions with every meal.

In the 1930s, the source of influenza was discovered to be viruses, not bacteria. By the end of the decade, in 1938, Jonas Salk and Thomas Francis developed the first vaccine against flu viruses. Today, about half of Americans get an annual flu shot. According to Phil Dormitzer, former Vice President and Chief Scientific Officer for Viral Vaccines at Pfizer, one of the key challenges in developing better flu vaccines is to “tap into modern understandings of immunity to make flu vaccines that are broad, powerful, tolerable, and convenient, so that people continue taking them every year.”

In recent years, an aspect of Spanish flu has resurfaced in a beneficial way: Researchers have tested Spanish flu survivors’s blood for possible clues to fostering immunity to modern incarnations of bird flu.

—Johnna Rizzo